The Secrets of the Rolle Canal

|

Funny story: When Boat Stories caught up with Adrian Wills to find out how the restoration of the Rolle canal sea lock was going, he sent us some pictures of what he thought were early morning poachers out on the river Torridge. It was us – filming our river story. And it was proof that Adrian is often up with the larks, working away on his epic, project of a lifetime. Below is an edited version of an article I wrote for Devon Life, published May 2014.

From the 1700s, packhorses carried

sand (full of crushed shells) from North Devon’s beaches inland to improve the

quality of the acidic soil for farming. The journey, across difficult terrain, was

slow and arduous so Lord Rolle tasked engineer James Green to build the canal.

The tubs carried limestone which was burnt in limekilns and spread on the land.

The canal originally stopped at Torrington. But the townsfolk

were worried about the competition and refused the sale of ‘manufactured goods’.

So Green continued digging taking the canal to Rowes Moor (now Rosemoor) and on

to Darkham Weir, six and a half miles in all. Ball clay from quarries like Peters

Marland headed back to sea and across to the Potteries, where it was used by

famous names such as Wedgwood.

The path ends at a roving bridge near Beam Weir. At this point the canal cut across a big loop in the river, the canal and the river swapped sides, so the horse on the tow path had to change sides too. A roving bridge is designed so that the towing rope doesn’t need to be unhitched. I stared at the bridge trying to work it out and decided they had to unhitch the rope from the horse’s headcollar. “No,” Barry explained, “the horse crosses the bridge but comes back down the same side, before going under the bridge and the rope is simply thrown over.” Amazingly, this was simply another bridge on the Tarka Trail, until a society member spotted the rope marks worn into the stonework. I was beginning to understand why the adventure is so addictive. It isn’t just about crawling through tunnels or even tracking evocative place names: Annery Kilns, Dock and Quay cottages in Weare Giffard or Taddiport. Look closely at an ordinary flight of steps in someone’s garden and notice how they’re worn by the passage of feet. A wooden rail found in the river bank once carried the lime wagons. As we walked, Barry found a long metal pole with a looped end, hidden in some bushes. I was in the zone and excited. I thought the loop was designed to take a horse’s rope. Barry wasn’t giving anything anyway. Not quite. Because hidden among the trees (where Dave pointed) Adrian and Hilary Wills have been quietly restoring the sea lock. It’s an epic, hugely ambitious project. When I asked Adrian why he’s devoted much of the last twenty-five years to a forgotten ruin, he replied “because it’s there.” When the couple first bought the land there was little sign of the canal. Adrian’s eureka moment came when he found a coping stone “peeping out”. He tugged at the turf and “it peeled off like a carpet peeling off its runners,” revealing the wall of the lock chamber. The lock gates were donated but as volunteers dug deeper into the silt they found the original paddle gates, set into the wall, which slam down like a guillotine to even out the water levels either side of the main gates. Adrian flushed water through to clean out the tunnel and find the seaward entrance and otters began to use the tunnel to swim around the lock gates.

Using old photographs, Barry and Adrian are building replicas of the original tub boats. Barry climbed into the tub to demonstrate how the helmsman steered the boat. He mused whether the metal pole we found near the trail might be an original centre pole, a bit like a mast – for securing the horse’s tow rope. I wondered if he’d placed the pole there to tickle my imagination. It was raining and the restored sea lock was definitely trying to hold water. My vision of a canal full of water was not so far off - thanks to those passionate enthusiasts working away to remind us of the Rolle Canal’s former glory. More information www.therollecanal.co.uk GUIDED WALKS ALONG THE ROLLE CANAL see our events page or contact [email protected] |

Walking the old tow path by the canal bed Walking the old tow path by the canal bed

I first heard of the Rolle Canal,

linking Torrington to the sea, about five years ago on a boat trip along the

river Torridge. Dave Gabe, our skipper, pointed through some trees and spoke of

an ancient sea lock, although we were nearly three miles inland from Bideford. I

imagined a canal, brim full of water, slipping silently through the woods. Dave

shattered this image, saying the canal had been destroyed by the railway over

140 years ago. But for the past ten years, members of the Rolle Canal Society have

been on a Boy’s Own adventure,

hacking through vegetation, crawling through tunnels, slowly revealing the

secrets of the canal. Now thanks to North

Devon’s Biosphere Life’s Journey project which has opened up viewing points

along the Tarka Trail, it’s an adventure anyone can take. I was treated to a guided

tour courtesy of society members: Anthony Barnes, Barry Hughes and Adrian

Wills.

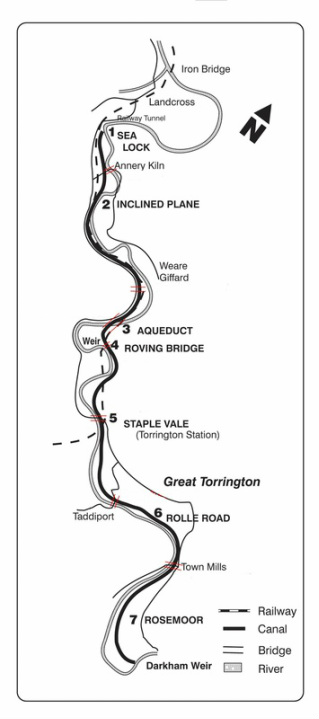

We met at the Puffing Billy, just outside Torrington and one of several stops on the Tarka Trail where you can hire bikes. About 400 metres up the trail, towards Bideford, bike racks mark the entrance to a new permissive path (opened up by Clinton Devon Estates) which follows the footprint of the canal. I was searching for the canal when I realised I was staring at it, running below us on our right, cut like a long terrace into the wooded hillside. I was struck by how narrow it was – only six feet wide at this point. To our left was a steep drop to the river, about ten metres below. We were walking on the old tow path, once trod by weary horses pulling a string of wooden ‘tub boats.’ As Anthony and his teams of volunteers slashed their way through wild undergrowth and shored up the old bank, picking up fallen stones and replacing them, like pieces of an ancient jigsaw puzzle, they must have felt like the pioneers who began building the canal in 1823.

We reached the famous five-arched

aqueduct which carried the canal over the river Torridge: the same canal bridge

under which Tarka, the otter, was born and frolicked in the shallows. There’s a

wonderful view of the aqueduct from the Tarka Trail and it’s still one of the

best places to spot otters today.

Next stop: the inclined plane, apparently built to save water. Surely in Devon, we’re not short of water? Tony laughed as he showed me part of the stone vault which housed the giant water wheel, “it’s all about having water in the right place.” An inclined plane is a ramp, lined with rails, to haul boats up or down in order to join two different levels of canal. At this point on the Rolle canal, it would have taken five locks to climb up the from the river meadows to the forested hills. The boats were hauled by a continuously moving chain, looped over a huge pulley at each end, powered by a giant water wheel. This noisy, spectacular feat of engineering drew crowds from the local hostelry to watch the sport. On the way down to the sea, boats, fitted with iron wheels, queued in the holding basin. The helmsman had to hook his boat to one chain to haul it over the sill (designed to prevent water spilling out of the canal). Then he had to hook on to the moving chain quickly to stop his boat careering out of control down the slope and crashing. At the bottom, the tubs leapt over another sill and splashed in to the canal basin. From the inclined plane the canal ran to Torrington without the need for locks or planes, so when the railway was built the canal provided the perfect bed. Amazingly, Lord Rolle didn’t object to the railway tearing his canal apart – once again he saw how it would benefit his tenants. Today the same flat bed makes an easy cycling trail. So the Tarka Trail runs along the old railway or the old canal, which is why it can never be fully restored and why a canal, full of water, will remain a figment of my imagination. |